BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

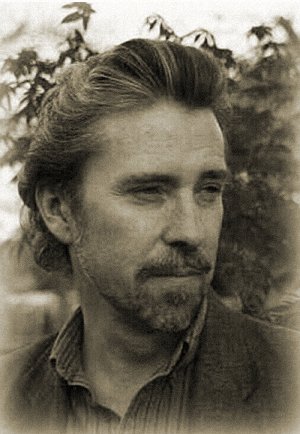

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

The Perishability of Metaphors is Copyright © 2017 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

the perishability of metaphors

Published in Black Static #56, Jan-Feb 2017

The other day while Mary and I were changing our bed sheets, tossing pillows sideways, cats scattering, resentful, I tried to remember a Nabokov metaphor.

One of my favorites of his, because it's the type of comparison so obscure, yet so true, you wonder how he ever discovered the connection.

Like a lot of us, I was a precocious child. Discovered Nabokov when I was twelve.

My parents were the best type of parents, utterly indifferent about what I read.

Whenever my mother changed the sheets on my bed, chances are there'd be a closed volume of, for example, The Story of O lying on my nightstand, bookmark a torn strip of newspaper sticking its tongue out at her as she lovingly tucked the stretched white corner of a bottom sheet under the mattress.

When I moved out of my family home in my early twenties, I left my books behind. I didn't need them anymore--they were in my head. Whenever I'd come back for a visit, I'd see all my childhood books proudly displayed on the wall-to-wall bookcase in the dining room, without my parents ever cracking one open to read its contents, so that watching down on my parents' guests while the mashed potatoes were passed around were the unexpurgated works of the Marquis de Sade, Last Exit to Brooklyn, Naked Lunch, Our Lady of the Flowers, and much, much more.

The metaphor from Nabokov I was trying to remember had to do with a comparison between a drive-in movie screen, and soapy dishwater.

But I couldn't remember the actual quote, and it bothered me I couldn't.

Two of my shelves in my upstairs study are filled with books by Nabokov, or about him. One early morning, me up, but not yet the sun, I sat in my swivel chair, went through some of those books, eyes rapidly rolling down each tower of text, looking for 'drive-in' or 'soapy'. As a child, I used to pride myself on being able to quickly scan a tall rack of paperbacks at a drugstore, immediately knowing if I wanted to lift a paperback out of its square metal display space on the rack, before some other reader standing on the opposite side of the rack revolved my choices away from me.

But I could not find the metaphor.

I emailed Brian Boyd in New Zealand, the preeminent Nabokov scholar, not really expecting a response, but in fact he did answer me within a few hours, a friendly, gracious email that supplied the quote and cited its source (Lolita).

"While searching for night lodgings, I passed a drive-in … on a gigantic screen slanting away among dark drowsy fields, a thin phantom raised a gun, both he and his arm reduced to tremulous dishwater by the oblique angle of that receding world…"

What fascinated me about the metaphor is that its capability to evoke its comparison is slipping into the past.

Nabokov is talking about how a moving image projected onto a giant white screen loses its visual sense once it's viewed from an increasingly oblique angle, so that eventually it becomes the chaotic nonsense of soapy water.

But as more and more drive-ins close, a modern reader's ability to visualize the metaphor is diminishing. Unless you've actually driven past the side of a drive-in screen at some point in your life while a movie was being projected, once a common occurrence, it's hard to understand what Nabokov is saying.

The perishability of metaphors.

One Saturday in the mid-Nineties while Mary and I were working outside in our backyard garden, arms covered in dirt, sweat trickling out of our hair, I took a break under the tall trees at the rear of our property, sitting on a white plastic chair where there was at least some shade from the hot Texas sun, lighting up a cigarette, leaning back. Lifted from the green plastic table beside our chairs the wristwatch I had unstrapped hours earlier, checking the time. Another hour, and we'd be able to stop for the day, uncapping two bottles of Spaten Optimator, tilting back our heads, gulping down that cold darkness.

Once we had all the plants, flowers, blooming vines in place, we were going to wind grass paths around the beds, like a park. The grass we were going to use, because it does well in shade, was … I drew a blank.

Bent my head. What was that grass called? Such a common name! But I couldn't remember it.

That scared me.

Once Mary came over, I asked her the name of the grass.

Standing in her jeans with an orange-handled trowel in her right hand. "St. Augustine."

Over the years since, like a test, I sometimes ask myself what the name of the shade-tolerant Southern grass is. Always reassured when I can come up with the name.

The perishability of memory.

Like most of us, I've probably seen a thousand horror movies over the years. Many have a depressing sameness to them. But there are those rare moments in a few films where we suddenly do see horror, feel it up our spines, and those moments are worth all our years of searching.

The Night of The Living Dead, the young couple trying to get gas into the truck so the group can leave, Ben waving a torch to keep the dead at bay, and it all goes horribly to shit, truck exploding into flames with the couple still inside, the devastation of what just happened captured in Harry Cooper's hopeless stare from behind a boarded-up window.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, two members of the group knocking on a front door, no one answers, the man ventures down the front hall, the woman hanging back, gets to the doorway at the end, and Leatherface, in his first appearance, sliding into view, slamming a long-handled hammer against the man's head, dropping him, the man's feet vibrating on the floor like a cow in a slaughterhouse.

Or the saddest, most disquieting moment: The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Miles comes back from exploring the hilly area surrounding the dark, dripping cavern where he and Becky are hiding from the pod people, lies on top of Becky, kisses her, so grateful they escaped being turned into pod people, and then the slow pull of his lips off Becky's, looking down at her cold eyes, realizing only he escaped.

To love someone, and then realize that even though they're still there, physically, they're gone.

My mother had Alzheimer's.

She had always been an anxious woman. Looking back at the telephone calls between me in Texas, her in Connecticut, once she had been diagnosed, I could see how her mind had been slowly dripping away. Apologizing about extraordinarily trivial offenses she thought she had committed decades prior.

After her competency hearing, after she had been court-ordered to a nursing home, I called her one night from our kitchen, nervous, Mary nearby, rubbing my back.

It took a few minutes of confusion before she was put on the line a thousand miles away.

My father reassured me he went out several times a week to where she now lived, each time sliding his old hand under the curves of her body, to make sure the staff hadn't left her lying in her own urine.

I didn't expect her to recognize my voice, and indeed she didn't.

What surprised me was that I didn't recognize her voice. It was low, masculine, guttural. Not at all the lilting tone from our family dinners, where she always kept the conversation going, my childhood books looking down on us.

That was the last time I ever spoke to my mother. The last time she ever heard my voice, and I heard hers, though neither of us recognized the other. It had become too oblique an angle.

The next time my father called, black phone ringing on the white kitchen counter, it was to let me know my mother, the only mother I ever had, died.

The perishability of mothers.