BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

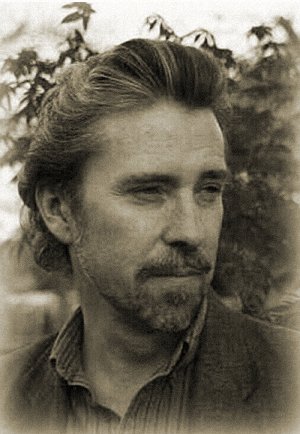

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

A Mask for the Bones Beneath Copyright © 2018 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

a mask for the bones beneath

Published in Black Static #66, Nov-Dec 2018

I know this has happened to you.

You're finally back in your home, after having to deal with people for all those brightly-lit work hours, front door shut and locked at the end of the long day, wanting to relax, the time when you can finally do whatever you want to do, not what other people want you to do, and in your happy loneliness you're watching a movie. Isn't watching a movie, in some ways, like listening to our parents when we're still really young, crawling across carpet?

And there's a scene in that movie where one of the actors is wearing a t-shirt. The t-shirt has a message printed across the front, but because of the camera angle, or an additional article of clothing the actor is wearing over the t-shirt, a dress shirt, a jacket, you can only read part of the message. And as the scene progresses, exchanges of dialogue, the lighting up or stubbing out of a cigarette, the passing of a rubber-banded bundle of money from one hand to another, you see that actor from different angles, and all you're paying attention to now is trying to read the full message on his or her t-shirt. But you can only catch glimpses of the words. Eventually you realize the message, whatever it says, is printed in three lines across the actor's chest. But what does the complete message say?

And often you sense the director is playing with you, letting you see the top line, the first two words on the left of the middle line, but still deliberately withholding a reveal of the entire phrase. Sometimes, in the final shot, you do at last get to read the entire phrase. But sometimes, you're never shown all the words, and what was written on that character's t-shirt in that scene is forever a mystery, never revealed.

A lot of evenings, during Summer, during my orange childhood, night sky filled with the white iridescent spread of stars, I'd eat at my maternal grandparents. Since they lived on the ocean, and my grandfather would routinely go out in his rowboat, dinner would often be fish. One time he rowed back to his grey dock having trouble swinging the oars, because he had snagged his fish hook into his right palm. Once he secured the row boat to the dock, climbed out with the awkwardness of old age, flounders flapping in the bottom of his tin pail, he stood on the dock, in front of me, reached into his sagging left trouser pocket, pulled out a small pocket knife, unfolded it, matter-of-factly cut its sharp blade tip down into his palm, red blood pooling out, to yank out the barbed curve of that hook. Nowadays, that would be an expensive outpatient surgery, but back then, amid the sour death smell of the ocean, below the huge blue darkening sky, it was just him blowing against his palm, pressing his left thumb's upper pad against the wound.

The freshness of the fish on our dinner plates was a mask for the bones beneath, so when we ate fish at my grandparents', my grandmother would place a small plate of sliced white bread on the dining room table, next to all the ashtrays, in case someone swallowed a fish bone. The idea was if a thin fish bone got stuck down in your throat, the swallow of a piece of bread would dislodge it.

My favorite horror movies are the ones where the monster is only gradually revealed. The glimpses of the monster, a shadow against a white wall, an evocative rattling sound, are its mask. This helps explain the long tradition of masks and unmasking scenes in horror films. Masks represent what is being shown to us as artifice; the unmasking reveals the truth behind the artifice. It's only at the end of Lon Chaney's Phantom of the Opera that he finally removes his mask. This trope of lifting the mask has become more sophisticated over the decades. In Alien, the monster keeps changing shape, so that there is a continuous unmasking. In The Thing, the monster changes shape so many times you eventually realize you'll never be able to see its actual face, no matter how many masks it lifts, because perhaps there is no original face; it exists only in imitations of other faces. There's an excellent parody of this process of unmasking in Predator, where the monster is initially invisible, then unmasked as a wide-headed creature with dreadlocks, then unmasked again near the end of the film as its helmet hisses open and we see its true face underneath, then unmasked a final time as its fangs open in an aggressive display, mouth widens, and we see the inwards of its maw.

When Mary and I first moved to Maine, we rented an apartment on the top floor of a multi-family house on a side street of Portland. Our landlady, Mrs. Littlefield, such a Maine name, representing the property manager who owned multi-family houses throughout Portland, was a short, elderly lady who smiled a lot. Kind eyes. Wrinkles radiating outwards from her twinkling blue gaze. Her mask. One Saturday morning several months into our rental, Mary and I lying on the white sheet of our bed, so glad it was the weekend, top sheet pushed by our feet down to the bottom of the bed, smoking, starting to think about eggs, we heard, rising up through the stairwell outside our front door, Mrs. Littlefield talking about us with a neighbor on the first floor.

"Well, they're not at all friendly. No. They seem a bit stand-offish?"

To this day, I don't know if Mrs. Littlefield thought the conversation she was having with a first-floor tenant was unheard by anyone else, or if she was passive-aggressively letting us know what she thought of us, removing her kindly landlady mask.

I don't know who I am. That is my mask coming off. And if you're willing to remove your mask, and admit it, you don't know who you are. We know who we want to be, who we pretend to be, present ourselves as being, but we don't know who we truly are. I wrote once that we are born into two mysteries: The mystery of life and the mystery of ourselves, and we don't get to solve either mystery in the short gaming time we're given.

When I was a child I would sometimes wear cowboy gear. A beige shirt with brown leather shoulders, a cowboy hat with thin leather straps tied under my small chin. Gun strap cinched around my waist, holstering a green water pistol.

One time, when I was still a child, wearing my cowboy hat but old enough to know my grandmother was the kindest person I had ever known, I went down the front steps of her white porch, and my grandmother asked me to come back inside, because lunch was ready.

And do you know what I did?

I looked up at her from the bottom step, I pulled my water pistol out of my holster, and taking aim, I shot her.

The lowering arc of water squirted against the front of her flowered dress, below her breasts.

She raised her old, loving face on that white front porch, so many deaths ago. Surprised, disappointed. "Don't do that again, Bobby! It's not nice!"

I shot her because it was hard for me to believe anyone would be that forgiving. I was sure her kindness must be a mask. I grew up like any kid where you feel you aren't understood, aren't being treated fairly, everyone is against you, parents, teachers, friends, pedestrians, librarians, and this was the one time I decided to test her kindness by squirting my water pistol at her.

And me, in my cowboy hat, do you know what I did next?

I squirted that dear old woman again.

I was trying to read what was written on her t-shirt.