BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

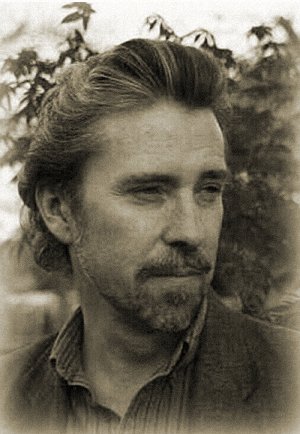

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Unfair Apocalypse Copyright © 2020 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

unfair apocalypse

Published in Black Static #73, Jan-Feb 2020

John Updike reviewed Walter Abish's 1974 novel, Alphabetical Africa, in The New Yorker.

The book is an example of what is usually referred to as 'constrained writing', which is writing that has to follow certain self-imposed rules (much of classic poetry is constrained writing, in that it has to conform, for example, to meter and rhyme).

In Abish's case, he decided he would write a novel of 52 chapters. In the first chapter, all the words had to begin with the letter 'A'. In chapter 2, 'A' or 'B'. And so on. After the twenty-sixth chapter, where words beginning with all the letters of the alphabet may be used, each subsequent chapter removes words beginning first with 'Z', then 'Y', etc.

In his review, Updike writes, "By the time [Abish's] verbal safari reaches 'G', Abish can make, at length and almost fluently, observations worthy of Moravia's."

But under the constraints imposed by the author, once the novel passes that mid-point of the 26th chapter, and letters are one by one taken away, we are eventually whittled down until we return, and end, with a final chapter where once again all words are limited to those starting with 'A'.

Like life, where you gradually gain it all, taller, stronger, braver, grinning at a dinner table surrounded by friends, then slowly lose all that straightness of spine, all those possibilities, bit by bit, to poor health and obituaries.

Every once in a while, for the length of a sentence, we write a great line. All the right words tumbling into place like cherries in a slot machine.

Bob Dylan said once he wrote the song stanzas he had to write to get to the stanzas he wanted to write. Just like sometimes you have to have a conversation with a secretary about this crazy weather before you're able to pass through the door of the office behind his desk to talk to the person you came here to meet.

Of all the serendipities that happen on the page, probably the most famous is Shirley Jackson's opening paragraph to her 1959 novel, The Haunting of Hill House. The paragraph's been quoted and analyzed for over half a century.

'No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality…'.

But if that paragraph is arguably one of the finest paragraphs ever to open a novel, which of its words are the best? The key sequence?

I say it's the final ones: '…and whatever walked there, walked alone'.

We don't always know when something new has started.

Mary and I were going about our usual lives, having fun, cooking delicious meals, watching great movies, going upstairs in the late afternoons with a drink to pursue our individual interests, culminating around seven when we'd watch some videos together then go downstairs for dinner, when I noticed Mary started to get more tired each day.

Like I said, it was next to nothing at first. A little longer for her to get out of bed, then a decision to stay in bed while I made our breakfast, but then it became more pronounced, to where I had to help her up the stairs each afternoon.

One night after midnight I heard a disturbance in the dark, turned on my bedside lamp, and Mary was no longer beside me on the sheets.

She had fallen out of bed.

Even more worrying, even with my help, the arms of my blue and white pajamas reaching down, she couldn't get back up into bed.

At some point that scary, disorienting night, both of us exhausted, we decided to do something you only do as a last resort.

We called an ambulance.

Death is often considered to be the underlying theme of horror, but I think the theme of aloneness is just as central to the genre.

We die alone, even when surrounded by a hospital room full of faces, many of which look like younger versions of us.

This theme of aloneness plays out in different ways within horror.

Often, it appears in apocalyptic fiction. After all, it's not called We Are Legend. The world has ended, and one person, man or woman, must try to continue on, even though everyone they know is gone. Can you imagine how lonely that would make a protagonist?

Sometimes, it's situational horror. The world is still going on, but without you. Which in many ways is an even worse aloneness.

Carol Kane being terrorized by a psychotic killer in 1979's When a Stranger Calls, alone in her parents' home, updated by Wes Craven in 1996 for Scream when Drew Barrymore finds herself in the same situation.

James Franco trapped away from everyone he knows under a boulder while mountain climbing in 127 Hours; Robert Redford in All Is Lost trying to survive out at sea by himself after his boat collides with a shipping container in the middle of the ocean.

It's not a global apocalypse. It's in some ways something worse-a personal apocalypse.

The rest of the world is still able to cut each other's hair while slightly drunk, bare feet stepping sideways while comb-lifting a new spread of hair, make dinner together, and scratch each other's back. Only you won't, probably ever again.

It's an unfair apocalypse.

After an echocardiogram and some exploratory surgery at the hospital, the cardiologists assigned to Mary's case realized one of her four heart valves was leaking. Badly. This had probably been going on for a while. It was only pumping sixteen percent of the blood it needed to. Mary was close to heart failure.

Her cardiac surgeon scheduled open-heart surgery. After some more exploratory surgery, it was determined the surgeon could perform a less invasive procedure than the standard surgery, snaking a replacement valve underneath her ribs, rather than breaking her ribs apart.

Mary had the surgery on a Wednesday. By the following Saturday, she still had not come out of the anesthesia. Which was a concern. One of the attending doctors ordered Mary's hospital bed be wheeled downstairs where she'd have a CT scan. He turned his face towards me as my unconscious Mary was wheeled out. "There might be brain damage."

And I had to think about what life would be like if Mary died. To be that utterly alone, after forty years of living together. To roll down our garage door, now only my garage door, walk into the kitchen, now only my kitchen, and make a lonely pair of sunny-side down eggs.

I went down the elevator, outside, into the parking lot, smoking a cigarette, praying.

Our lives end with us alone. Horror prepares us for that. It lowers its face to ours, looks into our eyes, and says no matter how much you loved, no matter how many friends you made, or children, grandchildren, great grandchildren you had, this is the moment where you alone take my hand, and you alone, with no one beside you, walk down that path. Whatever you see, that's what you get.

About an hour after Mary was wheeled away for her CT scan she was wheeled back into her hospital room, her attending doctor trailing behind. "We didn't find any evidence of brain damage. She's going to be fine." And was genuinely surprised when I burst into tears, in relief, turning away, hiding my scrunched face, my red eyes, between the raised fingers of my right hand.

Later that Saturday, Mary came out of her coma. Looked up at me, head nestled on her white pillow. Smiled. There's the smile of a stranger, smile of someone who knows you, smile of someone who loves you.

To be alone, to be utterly cut off from everyone else, nothing to look at but your own hands, the parts of your body you can see with your eyes, is, to me, the great buried theme of horror fiction.

Living so alone you don't mind getting bills in the mail, because at least it's something to do.