BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

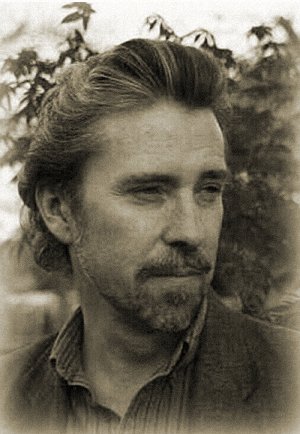

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

New World, Searching Copyright © 2017 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

new world, searching

Published in Black Static #58, May-Jun 2017

Norman Saylor, professor of ethnology at a local college, is creating a brochure to be used by the War Office, and with a "final staccato burst of typing", completes it. Good for him. He decides to celebrate his accomplishment in a rather odd way, by "snooping around in his wife's dressing room". It's an act of intimacy, albeit a one-sided intimacy, like reading someone's diary in the silence of their absence, or watching someone through a window without their knowledge. And he's smug as he does it. He's the type of man who is "sure nothing could touch the security of the relationship between him and Tansy", that anything he does find among his wife's personal effects, if it does involve him, will be flattering. He's that happy.

He has no idea, of course, that he's a character in a novel, in this case Conjure Wife, by Fritz Leiber. Leiber has another work which begins in a similar fashion, with a husband wandering around his home, wife temporarily absent, feeling happy, but not wanting to examine his happiness too closely, because he knows if he does, he's going to find reasons not to be happy.

Horror stories usually begin in one of two ways.

We meet the protagonist when they are already in the midst of horror, or meet them before the horror in their life starts.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, a movie I much admire, starts with a woman's corpse lying naked in a creek. So we know right from the beginning what we're in for.

By contrast, Takashi Miike's movie Audition (Odishon), is a happy, Cary Grant screwball comedy for its first reel. A widower interviews different women to find a new wife. And then it turns into one of the most unsettling horror films of the past few decades. And I prefer this approach.

If a horror story has horror right from the first scene, it loses some of its power. I love seeing things fall apart. If the pieces are already scattered across the floor at the beginning, it's not as interesting to me. I want to see that moment, and there is always that moment, when things go bad. A guy sitting on the bar stool next to you, after a pleasant enough conversation, says something demented. You exit the glass front of a store in a mall, happy with what you've bought, and people are running past, speckled with blood. One of the lessons taught early in painting is that if you want to show true darkness on your canvas, you have to add some lighter pigments, for contrast.

When Scream starts, Drew Barrymore isn't fearfully locking her doors and windows. She's making popcorn. What could be a happier activity?

Back in 2002, the company I was working at downsized. In a big way. Most employees were let go. I was asked to stay on, with the condition that I would now work from home. For years, Mary and I would commute together into Dallas each day, spending an hour and a half each morning in rush hour traffic, and about the same amount of wasted time at the end of the work day, slowly making our way, over different highways, home.

Now I would be home all the time, and Mary would have to make that brutal commute each day by herself. We hated being separated for so much of each workday.

In April of 2002, on a Wednesday, we talked over the phone, as we always did, at lunch. It was Spring, cool air scented with the reemergence of flowers. We decided to have a barbeque on our back patio that evening, once Mary was back home. I asked her what meat she wanted to barbeque, and there were long pauses in her answer. I thought that was a little odd at the time, but we could decide later. She told me she loved me, I told her I loved her, and we ended the call.

I went back to work at the computer in our bedroom, and five minutes later, the phone rang again. Checking caller ID, I saw it was Mary's number, so I immediately picked up the phone. Figuring she had decided what she wanted us to cook.

But instead it was Gayle, one of the women on Mary's staff. "Rob, I went into Mary's office to get her for lunch, and she was just sitting in her chair. She didn't acknowledge my presence, and her eyes were staring straight ahead. I think she's had a stroke."

By the time I arrived in the city, at the emergency room where she had been rushed by ambulance, Mary was being wheeled on a gurney from one curtained cubicle in the back rooms of the intensive care unit to another, for further tests. Her frightened eyes rolled around, saw mine in a swirl of strangers' eyes, and stayed with mine, as I held her hand, walking alongside her stretcher. Her sad face looking up at me, not comprehending.

It had been a stroke. A severe stroke. Afterwards, the neurologist who did a follow-up MRI told me that if he only had the radiographs to go by, he would have assumed the patient--Mary-- had died. He said the clot in her brain at the time of her stroke was "the size of an egg".

Mary no longer knew my name. No longer knew her own name. Because it was a left-side stroke, the entire right side of her body was paralyzed. Mary couldn't lift her right hand, couldn't wiggle her right toes.

Could not speak. Severe aphasia, a destruction of her language center. Words no longer made sense. Have you ever tried to remember the name of an actor, and it stays on the tip of your tongue? Every word in the English language was like that for Mary. When she was finally released from the hospital, nine days after her emergency admission, I drove her home and she immediately stroked the backs of our cats, happy to again be able to do something normal, but she had no idea what these loving, purring animals were called. 'Cat' was far too complex a sound, a concept, for her to be able to enunciate.

Those first few years after her stroke were a real struggle. Everything in our lives--everything--changed. Forever. It all suddenly got a lot more complicated than just making popcorn.

Mary did eventually get better, after years of speech and physical therapy. Never returned to the level she was at before, the head of her department, an officer of the company, someone who would routinely give speeches before large audiences, but she did at least return enough for us to be able to communicate with each other, in our own, new, way. And that's enough. It's more than enough.

I remember when I first read Leiber as a child thinking that idea of his about not questioning happiness too much, because there's always something to be sad about, now or looming, was good advice. And it helped me over the years, as art often can.

There's a passage by a contemporary of Leiber's, Richard Matheson, that also helped me a lot, particularly after Mary's stroke.

It occurs in his novel, The Shrinking Man. Scott Carey begins to shrink, and has to face terrible battles as he gets smaller and smaller, first with his pet cat, and then with the spider who lives in the basement with him. As he shrinks even further, it looks as if he might wink out, but then, in the beautiful epiphany of the last page of the novel, he realizes he will still exist, in a microscopic and submicroscopic world.

The love Mary and I had shared for decades wouldn't wink away because of her stroke. It would continue to exist, just in different ways.

"There was much to be done and more to be thought about. His brain was teeming with questions and ideas and --yes--hope again…Scott Carey ran into his new world, searching."