BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

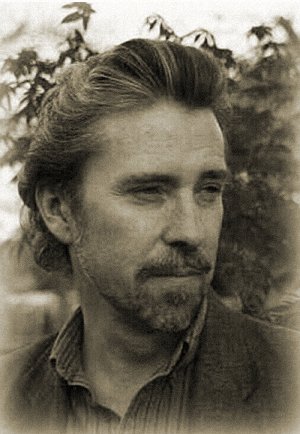

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Down on Paper Copyright © 2017 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Return to essays.

down on paper

Published in Black Static #61, Nov-Dec 2017

My father had piercing blue eyes. Most people who met him would mention those eyes, usually when he was in another room.

Fifteen years old, I burst through the back screen door of my family's home, after playing with neighborhood kids all morning, ravenous for lunch, hopefully a fried baloney sandwich on white bread with lots of mustard, but on this day my mother and father were sitting at the kitchen table, hands motionless on the Formica. I could tell in that moment of taking in how stiffly they were seated they had been waiting for me to come home. My dad asked me to step into another room. Away from my mother.

Following up the stairs, below the back of his pants. "What's going on?" Eyes avoiding mine, leading me into the striped bedroom he and my mom slept in, a room I never entered unless they were both out and I was in a mood to snoop. Asked me to sit on the edge of the parental bed.

I had no idea what this was about, except that I was apparently in trouble.

He opened the top drawer of the dark dresser, pulled out exhibit one, a thick sheaf of yellow legal paper, the top of each long paper curling upwards. "I was cleaning your room earlier today, and found this." Hoisting the thick sheaf. "What's this, pal?" (That's what he used to call me way back then, when I was young and he was young and everyone was young.)

It took me a moment to realize it was a manuscript I had been writing in secret in my bedroom, a pornographic novel modelled after the then-popular paperback series, The Man From O.R.G.Y., itself a take on the TV series, The Man From U.N.C.L.E., except it featured fewer murders and a heck of a lot more fucking. I bought the paperbacks at local stationary stores, and thoroughly enjoyed them (although shops would keep magazines that contained photographs of naked women, like Playboy, 'under the counter', not available to minors, cashiers thought nothing of selling pornographic books to teens. It was a more enlightened time. Most people were not concerned about protecting the innocence of children, because they knew there is very little about children that is innocent.)

Right away I knew my father was nervous. 'I was cleaning your room earlier today'. He never cleaned my room--that was my mother's job. It was clear to me he had worked up a script of what he planned to say, probably with my mother's help, and had flubbed one of his lines.

Trying to get back on track. "Do you know what homosexuality means?" (Because following the free-wheeling Man From O.R.G.Y. series, I had included a homosexual encounter in my masterpiece.)

He hefted my poor manuscript. "I can't throw this out. Because the garbage men might find it, and read it. I'm going to have to burn it."

Writers live a lonely life. That may be why we drink as much as we do. The coldness of a glass is at least some companion. It's nice to have a drink follow you, like a snout-dipping dog, sniffing the sidewalk, as you descend to the whiteness of a blank page, bouncing up with typing fingers. And we do like to type, don't we?

Henry Darger (1892-1973) was a hospital custodian in Chicago who spent 43 years of his life writing in secret, in his small apartment, a single-spaced story over 15,000 pages long usually referred to as, "In the Realms of the Unreal". His manuscript included several hundred drawings and watercolor paintings illustrating his tale. The main plot of the story concerns several little girls rebelling against an overlord who practices child slavery on a large planet around which the Earth revolves. What is interesting about his illustrations is that the little girls, often depicted naked, have male genitals, because Darger never in his life saw a naked female (which brings to mind the great British essayist John Ruskin. On his honeymoon, when his wife disrobed, he was stunned. He had no idea that was what the female body looked like. The marriage stayed unconsummated. Years later, when his wife left Ruskin, she wrote her father that Ruskin, "...had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was...the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening.")

After his death, when Darger's work was discovered, put out into the world, he was acclaimed. But I wonder how someone that private would have felt if people had publicized what he was doing while he was still alive.

A few years ago, in an interview, I was questioned about if, when I'm asked what I do for a living, I say I'm a writer.

And initially, when I was young, I did answer that yes, in addition to being a clerk, a bank teller, a claims processor, a plan analyst, compliance manager, consultant, I was also a writer. But then at some point I stopped telling people I was a writer. Why? Being a writer is about being completely honest, completely open about who you really are. Some of that's embarrassing, and a lot of it is not always flattering.

I had no problem writing honestly when it was strangers reading my work, but then one day my father-in-law told me he had stumbled across my site, had read my posted stories (some of which were sexually explicit), and had been surprised by that side of me. About the same time, a few people where I worked also discovered my website, and read the stories and my other pieces, most of which had nothing to do with sex, but all of which were still very personal.

By publishing on the Internet, my writing wasn't just being read by strangers. It was also, without it being my conscious intent, being read by family, friends, and business associates.

It's not just about you writing. It's about someone else reading what you've written, when that someone else may be a relative, a next-door neighbor, or the president of your company.

Did I really want someone I discussed the weather with while getting coffee at the office to know that much about me? I'm proud of every word I write. But it has cooled-off some relationships, and some people aren't as friendly as they used to be.

As writers, we all decide how much of ourselves we want to reveal. We hide behind characters. There's a great difference between saying an imaginary 'he' or 'she' did this, thought this, and 'I' did that, thought that. I so admire people who are willing to stand on stage and say, This is me. This is how weak I can be, how petty, frightened, wrong. Those are the artists you trust, because those are the artists who are trying to help. Part of art, certainly, is exposing yourself. Saying to the reader, You are not alone. You are not the only person who thought that sick thought, did that despicable thing. We are legion.

Once I left my family home, in my late teens, I never stayed in touch much with them. My dad's final years, he'd ask me often over the phone to send him something I had written, a story, an essay, because he was proud his first-born son had turned out to be an author.

I never did. Because I was afraid he would be disappointed again. Not understand me again. He died without ever reading anything I wrote as an adult, because I was a coward.

After my father spoke to me that afternoon about what I had written, and burned it, I waited a day, then started writing again. And just found a better hiding place. Or perhaps after discovering my new hiding place, my father simply realized I wasn't going to stop no matter what he said. I'd always be off somewhere, putting the words I wanted to down on paper.