lately

ralph robert moore

BUY MY BOOKS | HOME | FICTION | ESSAYS | ON-LINE DIARY | MARGINALIA | GALLERY | INTERACTIVE FEATURES | FAQ | SEARCH ENGINE | LINKS | CONTACT

www.ralphrobertmoore.com

the official website for the writings of

ralph robert moore

Copyright © 2006 by Ralph Robert Moore.

Print in HTML format.

Return to lately 2006.

but a boy

My father, Ralph Robert Moore Sr., passed away in his sleep Friday, September 22.

He was eighty-five years old.

He had been in poor health the past few years.

As often happens in life, in the midst of so many good things, there was one bad thing.

In my father's case, that one bad thing occurred about three years ago.

He was on vacation in Florida, with Kay, a wonderful woman he shared his life with after my mother died.

They were at a circus.

Going down the stairs to their seat, my Dad fell. He broke his hip.

He had his hip replaced in Florida, but the surgeon botched it. One titanium screw, so small and anonymous, hadn't been placed right. The screw soon came loose, inside him, causing my Dad a great deal of pain.

Once he was back in Connecticut, he had a second hip replacement surgery to repair the damage from the first. This second surgery was successful, but given that he had had heart valve replacement surgery a year prior, he was weakened.

He should have been walking normally, like his old self, in a month. Instead, three months after the operation, he was still winded after reaching the end of the hall of the assisted living facility where he had moved.

After that, he started bleeding internally. The doctors never found the source of his bleeding. Just treated it by giving him constant transfusions. The death of a thousand diagnoses. Then, his bones started breaking. He went under a number of surgeries to fuse his spine, to relieve the excruciating pain.

Even after all these operations, these crushing disappointments, he never lost his sense of humor. He wanted to keep living. To eat another meal (he raved about how good the food at the assisted living facility was), to go on another trip (he and Kay had been preparing to visit Las Vegas), to spend another quiet evening watching television.

I stayed in touch with him by telephone every few weeks. At the end of each call, I always said, "I love you, Dad." He always answered, "I love you, Bobby."

But I could tell he was departing. Each phone call I thought, and probably he thought, Is this the last time? And of course, one time, it was.

The Monday after his death, I went to a dermatologist about an unusual growth above my right eye. I figured while I was there I'd also have some moles on my left shoulder removed.

Since I was a new patient, I had to fill out a medical history. I had grown accustomed, under the column for Mother, inking-in, Deceased. But this was the first time ever I had to change what I put under Father.

I could have put in, I'll never hear his voice again, but instead, sitting among people with skin problems, I simply inked-in, Deceased.

The growth above my right eye turned out not to be cancer. Just a tiny wart. I sat at the edge of the tissue-papered examination table with my shirt off while the doctor looked at the growth with a jeweler's loop, then Sherlock'd around my chest and back. No malignancies.

Good news.

They removed the growth above my eye, and the moles on my shoulder, by freezing them.

The paradox of extremes is that the freezings felt like a tiny point of fire on each site.

The doctor told me to squeeze my eye shut, then tiny point of fire.

He moved to my shoulder. Tiny point of fire, tiny point of fire, tiny point of fire.

Once all the sites were frozen, it was easy to revisit them, he and his nurse assistant, dipping down with tiny scalpels, to excise.

Removing the growth above my right eye caused the greatest amount of bleeding.

The doctor had to press a cloud of white gauze against the gouge.

When he asked me to pull the gauze away, five minutes later, there was the prettiest bloom of red blood against the white gauze. One of the oddities of life, that red blood against white gauze just looks so pretty.

After the freezings and cuttings were finished I asked, "So that's it? It's resolved?"

The doctor nodded. "Until they come back. Which they will. But then we can do this all over again, each time."

Here's the remembrance I wrote for my Dad, for his memorial service:

I remember when our parents had dark hair. A time when they were younger than we are now.

When someone is fortunate enough to live as long as our father did, it's often difficult to see, in their face, anything other than the elderly person they've become, rather than the boy they were.

Dad grew up the youngest child in his own family, at a time when it was not unusual to have chickens and goats penned up in your backyard, as indeed Dad's family did. He went into the work force early, without finishing grade school, fairly common in those days.

And then World War II came. This boy who had never traveled farther than fifty miles from his place of birth was suddenly thrust into the world, serving in the Army in North Africa, China, Burma, and India, places that must have seemed, before the war, to be so exotic, so far removed from Greenwich, that they might as well have been on the moon.

I asked him once, years and years later, what one memory from those years he treasured most. He said it was the time spent in India, when he and his fellow soldiers would routinely swim in the local river with wild hippos. A boy can't get much further from backyard chicken pens than that.

After the war, he started work at the post office, as a letter carrier, a job he held until his retirement, and with that job security, was able to marry our mother. As their first-born, I remember those early years. Dad was a handsome, black-haired, blue-eyed man, full of life, and Mom was a beautiful, brown-haired woman. Like all young couples, they had to scrimp. I recall many Saturdays when Dad would pile the young family into the station wagon, then drive to our mother's parents, where Mom would ask her mother if she could borrow a couple of dollars to take the kids to the drive-in.

As they came into more money, our parents wanted to make our home look the best it could. I remember, as a small child, Dad and Mom inspecting a wallpapering job they had paid a professional paper-hanger to do in our front hallway, Dad deciding, as he looked at the repeated patterns of stylish mansions on the wall, that he could do the job himself, for a lot less. That revelation launched Dad into what seemed like a never-ending series of home improvements, re-wallpapering rooms and hallways, adding trim, repainting bathrooms, building terraces in our backyard, then starting all over again. He spent a good part of his time, like so many fathers do, trying to make life better for his children.

When I think of Dad, I think first of all of his sense of humor. I remember all of us sitting around the living room, watching TV, when Jackie Gleason on The Honeymooners or Don Knotts on The Andy Griffith Show would say something funny. Our father would laugh so hard his face would get bright red; continue laughing until it seemed like he was having trouble breathing. Once, when Mom had to work late at the bank, he challenged us three boys to a contest, in which he participated, to see who could do the best Twist, the latest dance craze way back then. In my mind's eye, I can still see the four of us males trying to comically outdo each other, swinging our elbows and hips. It's one of my fondest memories of childhood.

And I also think of how intelligent he was. He saw through hypocrisy, and retained throughout his life ideas that were probably far more progressive than many of his contemporaries. This natural intelligence made him intensely curious about our world. I remember when he and Kay, who contributed so much to our Dad's happiness in the final years of his life, visited with Mary and me in Dallas. We took them at one point to the Dallas Zoo. Although the three of us were moving through the exhibits at what I took to be a normal pace, we noticed Dad was lagging far behind. "He likes to read all the information posted about each exhibit," Kay told us. "He wants to know everything."

And indeed, he did.

Thomas Hobbes famously said once that "the life of man is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Our Dad knew that wasn't true, that life is about joy. And that's the greatest lesson he passed onto his sons, and to all who knew him.

He was a lucky man. He had a loving family, a wide range of friends, a broad spectrum of interests.

And unlike so many of us, he got the opportunity, when the old man before us was but a boy, to swim with hippos.

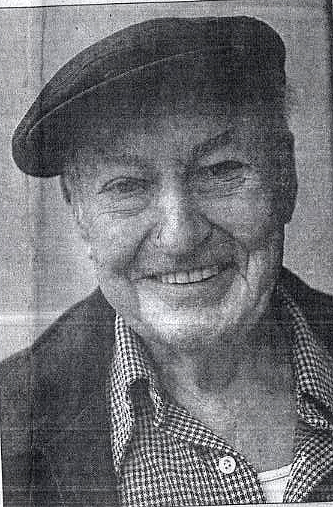

My Dad, a year before his death.